Edward Maguire Lahiff (Part Two)

America, Marriage and the Home Rule Question

Lahiff arrived in the United States late 1886, and for a year or two was employed by W.P. Rend & Company, Coal Merchants as a coal shoveler/handler. This was back-breaking, filthy work, repeated every week all year round. When delivering the coal the trucks would dump its load on the side of the street in front of the houses. The coal had to be carried in buckets and dumped into the coal cellar. Homes had coal chutes, often along the front porch. The coal would be dumped directly into the coal cellar. In an interview to the Chicago Tribune in 1901 Lahiff gives a brief life story, “Shanty on the Docks” and how he made his way from dock walloper to journalist. Edward Maguire Lahiff’s journalist career would see him in Chicago on the staff of the Chicago Herald and its successor, the Chicago Times-Herald and later move east and was for a time with the New York World. Lahiff achieved a country wide reputation as a reporter who covered "big assignments." Lahiff remained strongly involved in the Irish nationalist movement at home and in the United States, and wrote some of the most effective documents used in the Irish campaigns. He knew all of the noted Irish leaders, John Redmond, William O'Brien, John Devoy and others. During this time Lahiff would make frequent visits to his native sod, especially Aghada and its surrounding areas

“While he was doing this work, Lahiff made a little extra money by putting coal into the coal bins of private houses at the rate of 50 cents a ton. One of these odd jobs was to store the coal bins in the Convent of the Sacred Heart, and while busy at this work Lahiff got into conversation with the Mother Superior, who noticed that he was a man of good education, and suggested that he ought to be doing a better grade of work. He replied that he was doing the best he could. It happened that this conversation took place shortly before St. Patrick's Day, and the Mother Superior, talking soon after with the chairman of the St. Patrick's Day celebration, mentioned the fact that she had discovered a young Irishman, fresh from college, working as a labourer on the docks. It struck the chairman that this was a chance to add a picturesque feature to his celebration program. So he put Lahiff down for a speech, and gave to the Detroit paper the romantic story of the young Irish patriot who was living in the little dock shanty and earning a dollar a day by the hardest kind of hard work.”

Chicago Tribune 31 Oct 1901

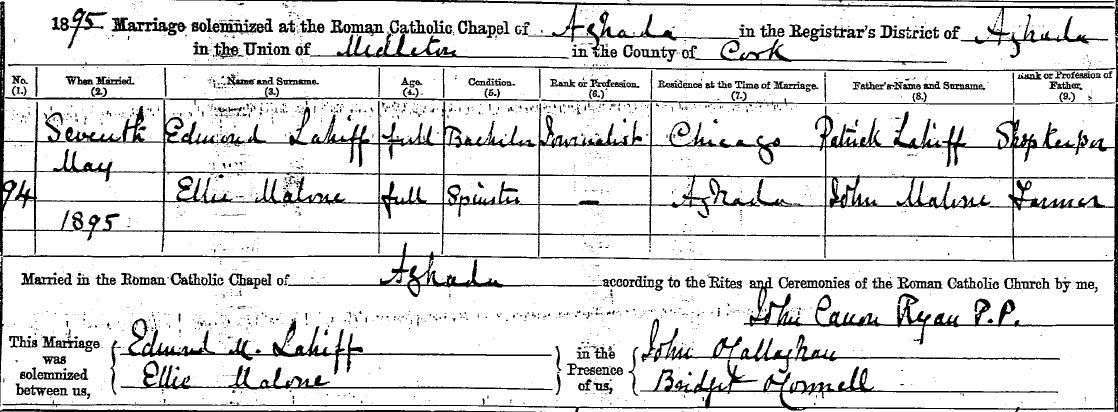

In 1895 Edward Maguire Lahiff returned to Aghada, Co. Cork Ireland, on the 7 May to marry Miss Ellen Malone (father John Malone and mother Mary nee White) a farmer’s daughter from Ballyhea and living in Aghada at the time.

A Pressman Married

Nuptial Mass was celebrated for the first time in Aghada last Thursday

The celebrant of the Mass was the Very Rev. Canon Ryan, P.P., the assistants being Rev. J. J. White C.C., and Rev. P. McAuliffe, C.C. The parish choir was in attendance, and floral tributes brightened the happy scene at the altar and shrine of Our Lady of Good Counsel, being laden with the choicest buds and blossoms of the season. In the ceremony itself there was, in a measure, an explanation of the crowded congregation ; but another reason explained the presence of so many, and it rested in the personalities of the young couple, whose lives more linked in the glory of the brightest of May mornings. They were Miss Malone, whose deft hands had adorned the altar before which she plighted her vows, and whose gentle ministrations among the poor and grief-stricken had been such a help to her respected and revered relative, the pastor of Aghada. Her piety and goodness were equalled only by the silent and modest manifestations of patriotism which taught the people of Aghada that in her own quiet way no truer Irish colleen ever whispered a prayer for Ireland's rights. In view of all this it was regarded as peculiarly happy that the young man who was to become her partner should be one whose life's story was stamped with incidents teeming with suggestions of all to which she had been loyal and devoted. In the early days of the Land League a schoolboy was soon recognised as one of the leaders in the barony of Imokilly. He was heard of through the fight until 1886, earning the honour of landlord enmity and Dublin Castle prosecution. The flag under which he struggled was gallantly upheld by the local president of the League, Canon Ryan, who with singular auspiciousness, was the officiating priest at the ceremony. The bridegroom of Thursday will be remembered throughout the country as Edward M Lahiff, of Whitegate, now on the staff of the Chicago Herald, who went to America nine years ago, and who signalised his marriage trip by securing the first interview ever accorded by Mr Gladstone to a newspaper man. After the dejeuner at Canon Ryan's the newly-wedded pair started to Killarney on their honeymoon. Among those from whom presents were received were Mrs O'Reilly, Mrs J W Hegarty, Mrs D Shanahan, Mrs E O'Callaghan, Mrs R O'Keeffe, Mrs Rohan, Canon Ryan, General Roche, Father White, Father McAuliffe, John O'Callaghan (best man), Miss O'Connor, Miss Wallace (Mallow), Miss Fox, Miss D O'Connor, Mr Motherway, Mr Desmond, Mrs J Fitzgerald (Youghal), Miss Fitzgerald (Youghal) Mrs Bate (Warrington, England), Miss Corkery (Worthing, England), J F Bate (Chicago), ES Bottum (Chicago), Miss Hassett (Ballyhea), Miss Holland (Cork). Mrs Trafton (Chicago), Miss Reilly (Chicago), Mr and Mrs J Murphy, Mrs Dunne, &c., &c.

Irish Examiner 13 May 1895

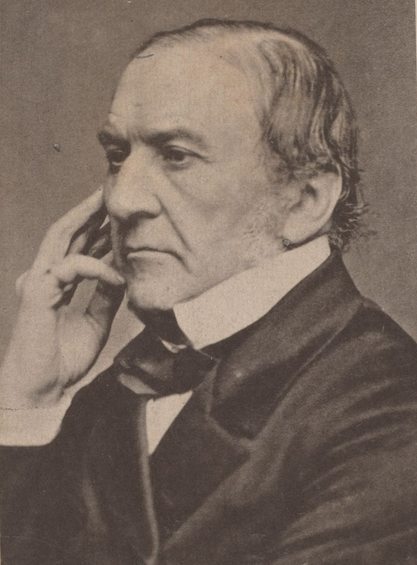

Marriage of Edmond Lahiff and Ellie Malone 7 May 1895

On the 2 May, five days prior to Lahiff’s marriage to Ellen Malone in Aghada Co. Cork, Edward Lahiff, who in the presence of the Right Honourable William Ewart Gladstone at Hawarden Castle in Hawarden, Flintshire, Wales (previously belonged to the family of his wife, Catherine Glynne), had secured a lengthy interview. This was the first time Mr. Gladstone ever consented to an interview with a newspaper representative. Prior to this journalist feat Edward Lahiff’s journalist skills and courage were tested during the “Homestead Strike” when he was hired out to the Carnegie Steel Company as a "scab" workman, in order to gain admission to the fortified works of that company. The dispute exploded in July 1892 when twelve people were killed when the striking workers attacked the Pinkerton detectives hired by the plant’s management as security guards. This incident became one of the deadliest labour-management conflicts in American history.

GLADSTONE INTERVIEWED

The Famous English Statesman Receives a Newspaper Man at Hawarden.

He Favours Any Movement for Irish Home Rule Even If Fathered by the Tories.

The British Electors Have Been and Are Bewildered By the Irish Strife.

Whenever Mr. Gladstone talks the world listens, says Edward M. Lahiff in the Chicago Times-Herald. In times of crisis the English people hunger for his words. Political England is passing crises the English people hunger for his of uncertainty since the unseen hands of party managers pulled the strings that hauled the sage of Hawarden from his place of power and set up the noble Derby celebrity in his stead. Attempts have been made by the English newspapers, by the resident correspondents of American newspapers and by the representatives of the British press associations, to get some hint from Mr. Gladstone as to his views on the political condition of the day. The private question of the situation, the issue on which the supremacy of one English party and the defeat of the other will be settled at the next general election, which will occur within six months, is, as is universally conceded, the disposition of the Irish demands.

Through all the throbbing months of enmity that have passed since his retirement from the premiership, Mr. Gladstone has mastered his tendency to loquacity on this main or any incidental topic. He has been praying to the little church at Hawarden in which one son ministers and close to which another sleeps beneath an eternal blanket of flowers renewed by loving hands from day to day, and he has been playing in his library or on the grassy lawn nearby with little Dorothy Drew. On one topic only has Mr. Gladstone spoken since his retirement, until May 2. He has railed with the old fire that glowed in his denunciation of the Bulgarian atrocities, against the outrages in Armenia, but he remained a sphinx in reference to matters nearer home. A recital of the conditions, circumstances and manipulations that resulted in the securing of my interview will prove interesting reading, here it will be sufficient to set forth what Mr. Gladstone said and how he said it.

As to why Mr. Gladstone should have succumbed to the efforts of an American newspaper man to get him to break a rule that he has rigidly adhered to in his political life namely, never to consent to an interview - It may be in a measure explained by his written expression, and part of the interview, “that the influence of the American friends of Ireland, if resolutely used, offers the most powerful and hopeful instrument" for the settlement of a schism, the existence of which he "bewildering” and demoralizing the party which he has so long brilliantly led, and, as it is hinted by shrewd ones in England, which he still yeans to lead again.

That there could be no carping about the authenticity of the visit to Hawarden and the securing of the interview. Mr. Gladstone with generous kindness consented to pen an address to the writer a few sentences of the interview, a facsimile of which ornaments this article, and in which the following passage appears:

“In my opinion the claim of Ireland might not improbably have been at this moment accepted and established by law but for the disastrous effect of this schism in bewildering the mind of the British electors, and the effect thereby produced in curtailing the Liberal majority of 1892. What I say is, I'll tell the Tories to go ahead, with my blessing and I'll tell them that any support at my command I'll render in favour of home rule no matter by whom it is fathered.”

The assignment to interview Mr. Gladstone was the last ever given by that prince among newspaper men and prince in the realm of fellowship, the late James W. Scott. “He has never been interviewed." said Mr Scott," and it may be because the English newspapers did not know how to get closer to the old gentleman. If you can't succeed, write a story when you come back of how you failed to secure it.

Four days in and around a Hawarden with an incidental trip to London, resulted in a little more than realizing the difficulty of getting near Mr. Gladstone outside the little church in which he escorts Dorothy Drew every Sunday, and whom he has called “the latest treasure life can offer me.”

On the fifth day the writer arrived with a letter on introduction from Justin McCarthy, M.P. discovered that he would not be allowed to present it. Gamekeepers refused to consider it and the lodge keepers were shocked and obdurate.

Rev. Dr. Harry Drew, Mr. Gladstone's son-in-law, lives close to the noted little church, of which he is assistant rector. He is father of little Dorothy, and as such is prominent in England. He is also kind, confiding and courteous. He saw in the visit of the American news-

paper man a very important mission. His ideas on this point were strengthened by corroborative assurances, and as a result at 5:43 o'clock, Wednesday evening, May 2, a representative of the London Press Association, who had been sent down to get the interview that the Times-Herald writer, was reported in London to be bent on securing, stood in agony at the outer lodge of Hawarden Castle and refused to acknowledge the writer's salute, who whirled by in a hansom on his way to keep an appointment with Mr. Drew with Mr. Gladstone.

Mr. Gladstone was at home, a waiting butler said. The superbly old gentleman had read Mr. McCarthy’s letter. It was a very kind letter but Mr. McCarthy has since been frank to say that he would not have written it had he thought it would be delivered.

Along the hall the keen edges of the hatchets glistened, the steel hatchet and silver hatchets, some for show and some for use, about a score telling of the woodman whose fame as a tree feller has travelled throughout the globe.

Mr. Gladstone was at home. He was standing by a small, round table within a few feet of the desk at which he has penned many a momentous document of state. He advanced a step or two, with a suggestion of feebleness in his limbs, but with the stamp of kingliness in his mien. "Americans are always welcome in England," he said, and Mr. Justin McCarthy's friends are particularly welcome.” The courtesy was fittingly acknowledged. Then Mr. Gladstone pointed to a seat near the little round table, a second close by he took himself.

"The impression seems to prevail in London, Mr. Gladstone that the Tories are gaining ground that they are likely to win at the general election. It also seems to be regarded as certain that the issue on which the Tories hope to fight and win is the Irish policy of the government, or, more directly, your home rule bill. Americans interested in English politics and friends of Ireland interested as such in the outcome, would like to get your views on the situation.”

"I never give interviews, sir." This with a polite firmness that seemed cruelly crushing. The air of reserve and firmness vanished like mist on a May morning. There was a boyish light in the big brown eyes, and the glow of a flower in the sunshine was on the majestic face. Mr. Gladstone was facing a window which looks into the little garden that adjoins the library. The visitor followed the old man's eyes to the window. Like a little robin chirping a greeting and perched on a window sill was Dorothy Drew. She kissed hands to her grandfather and went off like a bird. There was inspiration in the incident for a little dissertation on domestic felicity. There was an infinite wealth of tenderness in the way the bell tones uttered the words: "Dear little Dorothy."

"Ah; no," said Mr. Gladstone in gentler tones than he had previously declined, no one needs to be told on the Irish question. Why, with all your Irish blood, for I understand from Mr. McCarthy you are Irish-American-I am a better home ruler than you."

A merry twinkle accompanied this. He continued more feelingly and more earnestly: "What I have just said applies to you or any other Irish home ruler. An Irishman is a home ruler because of his love for his country. I am one because of the justice of the Irish cause in the first place and next because of my humiliation as an Englishman of the wrongs on Ireland."

"It would be interesting to know, Mr. Gladstone, what is to be the outcome of the present situation. I have already secured for the paper I represent written statements from the prominent men in the contending Irish parties. These will be published in the paper I represent and a statement from you accompanying them would be of exceptional interest. After a long pause Mr. Gladstone said: "I'll say this that the British electors have been and are being bewildered by the Irish strife. I'll say further that the most hopeful source of settlement as regards ending the unfortunate contention is among American friends of Ireland. This brings to my mind that Mr. De Pwee” 'Mr. Depew, you mean, Mr. Gladstone?” Depew, the New York orator? De Pwee, I thought it was, De Pwee. At any rate he told me that there were not 10 per cent of the entire voting population of the United States out of sympathy with Ireland’s struggle for her rights. In view of this appears to me that out of such a vast sea of sympathetic interest there ought to rise some hope, some effort ought to come to end the deplorable, the unintelligible scism that exists.

"Supposing no such settlement can be effected, Mr. Gladstone, what effect will the continuance of the discussion have on the English parties?"

English politicians will weigh, dissect, discuss and analyse this response when it reaches them: "Some talk of the Tories and some kind of a home rule measure. What I say is,” A long pause and a reflective look through the window at which little Robin Dorothy had appeared. After about a minute “What I say is, I'll tell the Tories to go ahead, with my blessing, and I'll tell them any support I can give I'll render in favour of home rule, no matter by whom it is fathered."

“Then you think the Tories are considering a home rule project?"

"I don't know that I ought to but, yes, the liberal-unionists are the ones who are most bitterly opposed to home rule in any form, in every form. They are the men who are most viciously, most uncompromisingly opposed to it. If the Tories fail to adopt some form of home rule, it will be because of the liberal-unionists. For the Tories to take up our programme and make their own of it would not be such a surprise to anyone acquainted with modern English political history. To me particularly a participant in or an observer of many reform movements during a long period, it is never strange or surprising to see the Tories steal our measures and make their own of them. Oh, yes, the liberal unionists are the ones who are most uncompromisingly, most bitterly opposed to home rule.”

Mr. Gladstone may be genuinely hard of hearing or it may be only diplomatic

deafness. At any rate he was as silent as tombstone and as unresponsive in look or gesture in regard to any questions that were put to him.

At the close of the interview proper, the writer, in thanking Mr. Gladstone for the Interview, expressed his regret that he could not take with him some unmistakeable corroboration of the interview. With great good nature he approached his desk and laughingly wrote his name and the date of the visit, May 2, 1895, across a picture of himself and his little darling, Dorothy Drew. The London Press. Association man was still outside at his departure. He went back to London without a word from Mr. Gladstone. The following day the writer received this telegram from the Association;

“Will you kindly supply London Press Association with substance of Gladstone’s statement?” An answer was prepaid but it did not cost much, it was simply this

“I guess not”

The Irish Standard Saturday 8 June 1895