A King’s Honour for the boy from Whitegate Co. Cork

Robert McGowan was born 3 April 1898 in the village of Whitegate, which is situated on the south side of Cork harbour. He was the son of James, a merchant seaman and Mary McGowan nee Ahearn. James and Mary had nine children including Robert but sadly by 1911 only four of the McGowan children had survived. They were Thomas, Elizabeth, William and Robert, all born in the village of Whitegate. In 1911 the census shows Mary McGowan (married) residing in house number 110 in Whitegate Town (Corkbeg, Cork) with her two sons William aged seventeen and Robert aged eleven. Within the next two years the last two McGowan boys would emigrate, William McGowan to the United States 6 April 1912 and Robert to the Royal Navy as a boy sailor 30 August 1913. Their older brother Thomas enlisted in 1900, also a boy sailor. Their sister, Elizabeth McGowan was married and living in the United States during this period.

In August 1913 Robert, at the age of fifteen, made his way to Devonport, England where it may have been possible that the young Richard met his brother Thomas who was stationed in HMS Vivid 1, the naval depot in Devonport. On 30 August 1913 Richard enlisted into the Royal Navy with the rank of Boy 2nd Class and was stationed on the training vessel HMS Impregnable. On the 6 December 1914 Richard (promoted to Boy 1st Class) and a new crew travelled to Liverpool to join the newly commissioned ship H.M.S “Hilary” (pennant number M90). The H.M.S. “Hilary” (original name S.S “Hilary”) had been requisitioned by the British Admiralty the previous September from Booths Steamship Company in Liverpool and converted into an armed merchant cruiser (AMC). “Hilary” was armed with six, 6 inch guns and two 6 pounder guns and a top speed of 14.5 knots and was part of the 10th Cruiser Squadron (Northern Patrol). “Hilary” provided a vital element to the Blockade of Germany, patrolling the seas between northwest Scotland, Iceland and Greenland. At 09:35 Wednesday 16 December 1914, H.M.S “Hilary” would weigh anchor and proceed on her maiden voyage with Captain, R.H. Bather and a crew of 243 men. Richard McGowan was one of twenty nine boys on board.

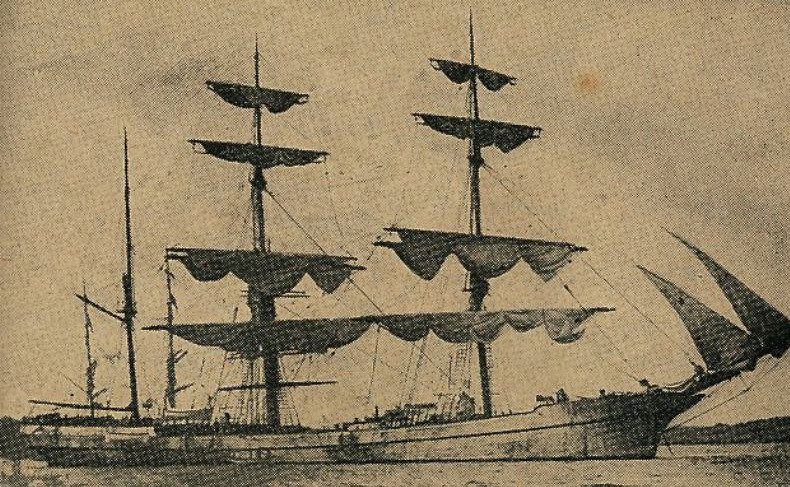

HMS Hilary, armed merchant cruiser - British warships of World War 1

H.M.S “Hilary” proceeded in a northerly direction towards the Faroe Islands passing through the Inner and Outer Hebrides into the Atlantic Ocean. On 19 December 1914 “Hilary” carried out her first boarding to carry out inspections. The vessel in question was the Norwegian steamer “Romsdal”. A sea boat was sent away with a boarding party consisting of Sub Lt Southcombe and seven men and the operation was completed in an hour. Over the next few days “Hilary” would carry out many boarding operations with ships mainly from Sweden, Demark, Russia, Norway and the occasional British or American vessels. The British ship in question was the SS “Tervoe” which was previously owned by the Cork Steamship Company, Ltd. and sailed under the name “Jabiru”. In 1899 it was sold to Limerick Steamship Company, Ltd., and was re-named “Tervoe”. Boarding inspections and the carrying of ships drills were continuous up until Christmas Day and on two occasions sighted HMS “Otway” and HMS “Oropesa”, both vessels were converted to armed merchant cruisers (AMC). Christmas Day 1914 on board “Hilary” was non-eventful. The day passed with the ship conducting various courses and speeds and the ships company had divine service that morning. “Hilary” was north of Sule Skerry Island, situated forty miles west of Orkney and thirty five miles north of the Scottish mainland.

The harshness and reality of the North Atlantic would soon strike into the crew of “Hilary” and the young Robert McGowan. On 26 December 1914 (St. Stephen’s Day to some and Boxing Day to others), the crew were back to war time reality. The day would commence at 5:10 with the sighting of SS “Zenet” from Gothenburg. The vessel was signalled and routine protocols were carried out and shortly thereafter was allowed to proceed on passage. As the day progressed the weather conditions were deteriorating with the wind blowing from a south westerly direction, with wind speeds reaching storm force ten (55–63 mph - 89–102 km/h). Conditions were becoming unbearable. The surface of the sea took on a white appearance. The waves became very high with a rolling effect, the sea became heavy with long overhanging crests, with the resulting foam in great patches blown in dense white streaks along the direction of the wind. The whole the surface of the sea took on a white appearance and visibility was affected. H.M.S “Hilary” was now in the grip of a storm. Then tragedy struck “man overboard”. It was early afternoon and the WL aerial was destroyed and a young man was swept overboard. This is every mariners fear. “Hilary” was now one hundred and ten miles from Suduroy which is the southernmost Island of the Faroe Islands. The crew of “Hilary” searched the treacherous seas but it was in vain. The lost soul was eighteen year old Private Andrew Waugh, Royal Marine Light Infantry from Callarder, Perthshire. Sadly his brother Private Robert Waugh of the Seaforth Highlanders would also perish in the war.

With the harsh reality of the North Atlantic and the loss of Private Andrew Waugh, H.M.S “Hilary’s crew continued on its patrol and by mid-morning on the 27 December 1914, would carry out routine inspections on the Swedish vessel SS “Nippo”, which had a cargo of timber from Christiania to Barry and SS “Oslo” (Wilson Line) with a general cargo from Liverpool to Christiania. SS “Oslo” would become a casualty of war. On 21 August 1917, she was torpedoed and sunk by the German submarine U.87, fifteen miles from Out Skerries, Shetland, while on passage from Trondheim to Liverpool with passengers and copper ore. One passenger and two firemen were lost. They were Fireman & Trimmer’s Thomas Clarke aged 41 from South Shields and Laurence Rossiter aged 33 from Wexford. For the next few days “Hilary” would carry out its main functions including exercised fire drills, collision mat drills and abandon ship stations. Further inspections of merchant shipping continued, which included S.S “Renvik”, “Margaret” and “Skarpsno”. Skarpsno sank in June 1917 when it struck a mine in the North Sea. The captain and two men were rescued but the remainder of the crews were lost. It was now one o’clock in the afternoon 30 December 1914 and H.M.S “Hilary” had sighted two sailing vessels on its starboard bow. “Hilary” proceeded towards the two vessels and made contact with the first vessel on its port side.

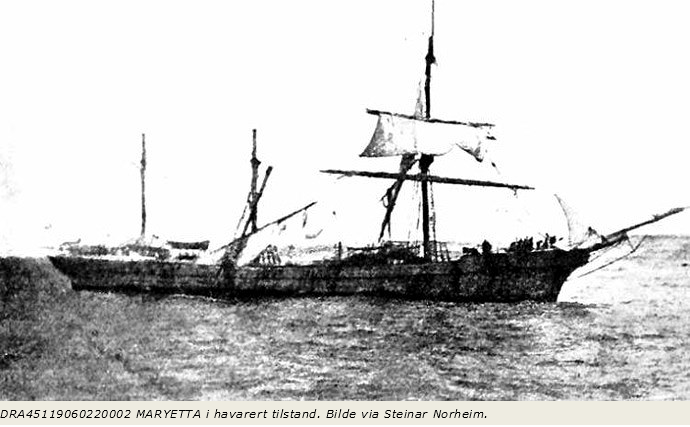

This vessel was the SV “Albyn”, a Russian four masted barque (a sailing ship of three or more masts with the foremasts rigged square and the aftermast rigged fore-and-aft) on passage from Drammen to Melbourne with its cargo of wood. After communicating with the barque Albyn, it was ordered to reduce speed and keep communications with “Hilary” and follow in its wake while it proceeded in a northeast direction to the other vessel, which was flying the Norwegian flag and was dismasted. While “Hilary” was on route to the seemingly distressed vessel it was instructed from the Rear Admiral “Alsatian” (10th Cruiser Squadron Flagship) to let go SV “Albyn” and continue on its set passage, to render assistance to the Norwegian vessel and when the weather moderated tow the stricken vessel to Kirkwall on the Orkney islands. By seven thirty that evening “Hilary” had located the stricken vessel. It was the Norwegian barque SV “Maryetta” on passage from Aalborg to Santos with its cargo of cement. It had been dismasted, losing her main and mizzen top-masts, fore top gallant masts and her main yard arm also came down. H.M.S “Hilary” stayed in close proximity until first light. The following morning two of Hilary’s crew boarded the stricken Maryetta. They were Sub.Lieutenant Osmond Edward Miles from Birkenhead and Signalman Frank Scott from Liverpool.

S.V “Maryetta”

As requested by the Master of the “Maryetta” the vessel was taken in tow, a wire hawser (wire rope) was connected to the cable of the stricken vessel and they proceeded to Kirkwall. The “Hilary” was making good its towing speed of approximately six and a half to seven knots but the weather was against the towing operation. The wind and sea were increasing during the night of 31 December - 1 January 1915 and by morning Maryetta’s fore topmast collapsed. As midnight approached weather conditions were deteriorating. The wind approaching from the southwest, with speeds now reaching between gale force nine to storm force ten, the North Atlantic was erupting. The waves became very high with a rolling effect of the sea becoming heavy with long overhanging crests, with the resulting foam in great patches, blown in dense white streaks along the direction of the wind. The surface of the sea took on a white appearance and visibility was affected. H.M.S “Hilary” and the crippled barque Maryetta were now in the grip of another storm. Until now towing operations were proceeding to plan but as midnight approached on the night of the 1 January the barque Maryetta fires a distress flare and begins to communicate by morse lamp, the signal “sprung a leak and sinking”. Until now no previous indication was given that anything was wrong with the stricken vessel. The “Hilary” released all its towing gear into the sea and directed its search lights onto the stricken vessel.

Just after midnight the “Maryetta” signalled that they were going to abandon ship and within forty minutes the crew of “Maryetta” (its crew of seventeen) with Sub. Lieutenant Miles R.N.R. and Signalman Scott were in the barque’s lifeboat which was safely launched into the wild North Atlantic. The following is a witness account by the chief mate J. Kristian,

“The sea was running so high that the boat over turned almost immediately. Most of the crew managed to cling to the ' keel and succeeded in turning the boat , but it filled with water and capsized again , The same thing happened on four other occasions , and each time some of the sailors disappeared . The British steamer, after much manoeuvring, succeeded in getting to the weather side of the upturned boat. By that time only six men were left of the original nineteen. Amongst the lost were the two British sailors.”

The Scotsman - Monday 4 January 1915

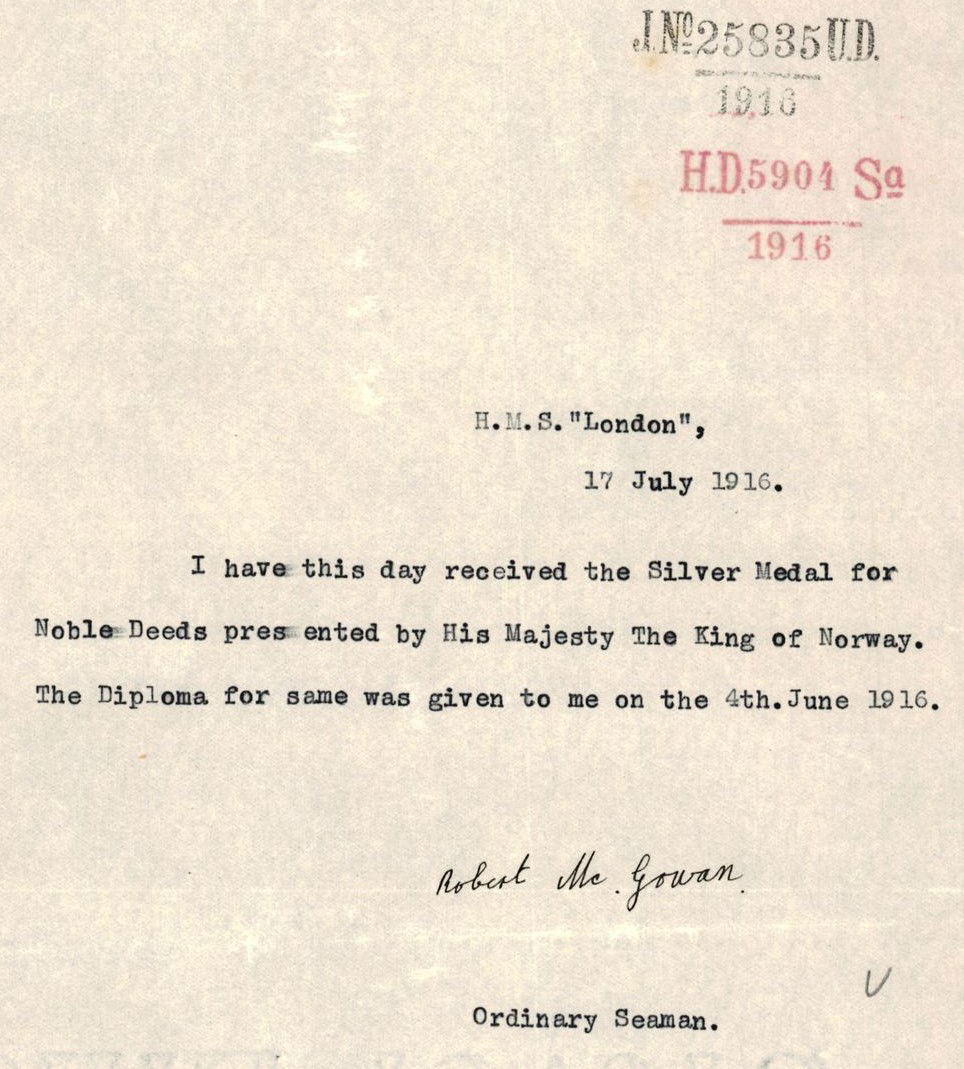

Within the hour the “Maryetta” had sunk, the position of the stricken men and its capsized boat was roughly marked by a lifebuoy with a calcium light attached. After much manoeuvring, “Hilary” was in position to lower its port sea boat and picked up the remaining six men, who included the master of the “Maryetta”. The following were the life boat’s crew, which had a combination of Royal Naval Reserve and Royal Navy, Officer in Charge Lieutenant R.N.R. Charles Maynard Wray, Leading Seaman R.N. Bernard Squibb, Seaman R.N.R Leander Green, Seaman R.N.R. Herbert Jones, Seaman R.N.R. John Newsham, Seaman R.N.R. Charles R. Vigus, Seaman R.N.R. Richard Jones, Seaman R.N. Albert Victor Walker, Boy R.N. Robert McGowan . These nine men and the Hilary’s Captain R.H. Bather would be recommended by the Norwegian Government the Medal for Noble Deed and were conferred by His Majesty the King of Norway (Haakon VII) for “having shown brave conduct at the rescue of the survivors, after the shipwreck of the barque, Maryetta.’’ On the 17 July 1916 a young man by the name of Robert McGowan from Middle Road, Whitegate Co. Cork was presented with a medal and certificate of merit for helping to rescue survivors from the Norwegian barque, “Maryetta" in late December 1914 - early January 1915, whilst serving on H.M.S. “Hilary”. On 17 July 1916 the medal and certificate were presented to Seaman McGowan in the presence of the ship's company on the quarter-deck of H.M.S. “London’’.

Ref: 2021/8427 Norwegian National Archives

By 5 June 1917 the three McGowan boys from Whitegate village were in the midst of the war. William who had immigrated to the United States in 1912 (living in Rochester, New York) was now drafted into the American Army. Thomas would spend all his war years on H.M.S Conqueror (1912 – 1920). He played his part, along with over a hundred men from Aghada, in the greatest naval battle of WWI, the Battle of Jutland, on 31 May, 1916, where tragically Aghada lost thirteen souls in this sea battle. Approximately seventy five miles off the Danish coast, a British naval force commanded by Vice Admiral David Beatty would challenge the German fleet, led by Admiral Franz von Hipper. More than 100,000 British and German seamen aboard 250 warships fought a brutal naval engagement. The British sustained heavy losses with the sinking of 14 ships, which included three battle cruisers and 6,784 casualties. The German lost 11 ships, including a battleship, a battle cruiser and the loss of 3,058 souls. After the traumatic experience Robert McGowan had with the Norwegian barque, “Maryetta" he served little time at sea during the war years and was discharged from the Royal Navy to Yarmouth hospital on the 23 April 1920. Due to poor health Robert remained in the naval hospital and was medically discharged into the care of his mother on 2 December 1924. Robert McGowan passed away in his native village of Whitegate on 16 October 1974. He is buried alongside his mother and brother Thomas in Corkbeg graveyard, just outside the village of Whitegate.

A special thanks to the following :

Rasmus Austad Christensen, Adviser, Norwegian National Archives

David Toms, Community Support Officer, Embassy of Ireland in Norway