HMS Hampshire, Lord Kitchener and the Aghada Connection

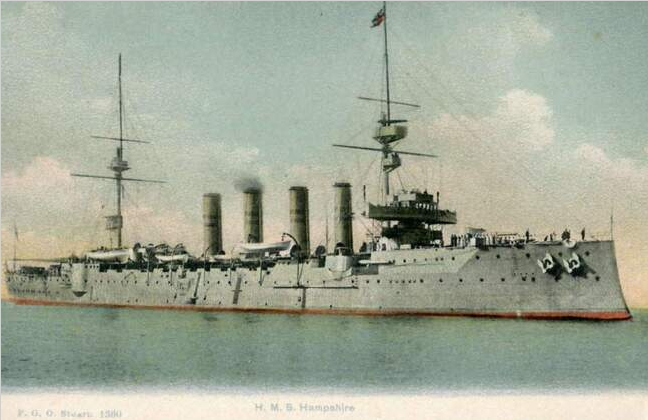

On 5 June 1916, HMS Hampshire left the Royal Navy’s anchorage at Scapa Flow, Orkney, bound for Russia. The Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, was on board as part of a diplomatic and military mission aimed at boosting Russia’s efforts on the Eastern Front. At about quarter to nine in the evening, in stormy conditions and within two miles of Orkney’s northwest shore, HMS Hampshire struck a mine laid by German submarine U-75. Only twelve survived.

There were at least 28 Irish sailors lost on HMS Hampshire, one of them was 194183, Leading Seaman Michael Flavin born 7 May 1882, Farsid (Rostellan), one of five brothers, all of whom served in the Navy. A year earlier his older brother John, a Chief Stoker in the Royal Navy(CWGC), while on leave was killed in a Railway fatality in Midleton and is buried in the old graveyard in Upper Aghada.

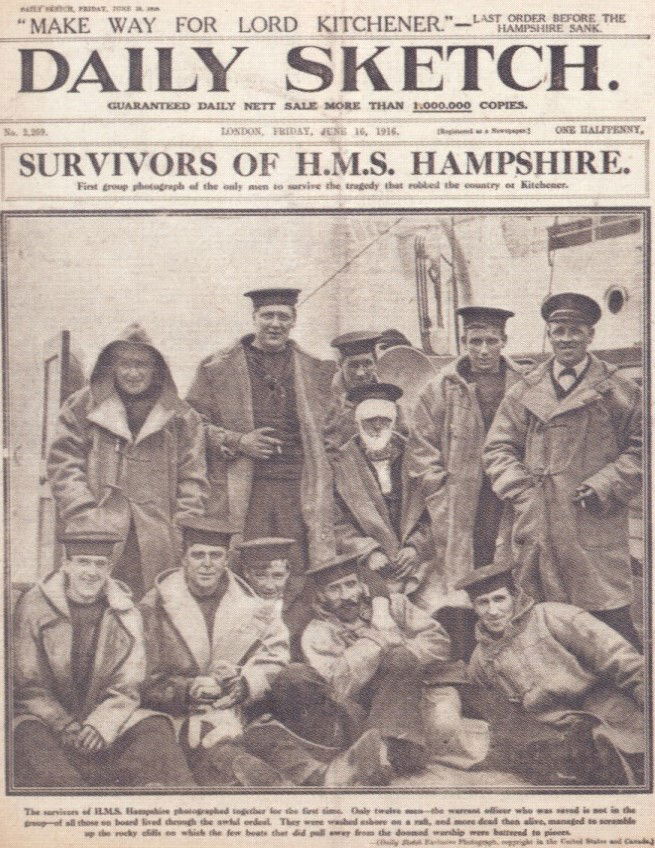

Of the 737 crew members and 14 passengers aboard, only 12 crew survived after coming ashore on three Carley floats. One of these men (the only Irishman amongst the twelve survivors) was 228580 Leading Seaman William Cashman, Born 22 April 1886, Ballinrostig, Co. Cork

“Only three oval, cork and wood Carley floats got away from the sinking ship. These rigid Carley floats were made from a length of copper tubing divided into waterproof sections, bent into an oval ring, then surrounded by cork or kapok and covered with a layer of waterproofed canvas. The raft was rigid and could remain buoyant even if the waterproof outer skin of individual compartments was punctured”.

| FATE OF THE HAMPSHIRE MINED IN HEAVY SEA. British Official.-The Press Bureau issued the following on Saturday evening: The Secretary of the Admiralty makes the following announcement: - A further report has been received from the Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet regarding the loss of H.M.S. Hampshire with Lord Kitchener and his staff on-board. It has now been established that the Hampshire struck a mine at about 8.p.m. on Monday last. The Hampshire was accompanied on her voyage by two destroyers, until the captain was compelled to detach them about 7 p.m. on account of the very heavy seas. It appears from the statement of the few survivors that the explosion shortly before eight p.m., the ship sank within ten minutes. Immediately on receipt of the news destroyers and patrol vessels were dispatched to the scene, and search parties were sent in motor cars to work along the coast. It was reported that four boats had been seen to leave the ship, and all the vessels that had been dispatched were ordered to look out for and assist these boats. "In spite, however, of all these measures," the Commander-in-Chief concludes, "with the deepest possible regret that there can be no doubt that the boats were wrecked in the heavy sea on a lee shore, and that beyond twelve survivors who got to shore on a raft, all hope must be abandoned." Freeman's Journal 12 June, 1916 |

During this time William’s brothers were also serving, Joseph born in 1895 serving in the Royal Navy (Battle of Jutland, H.M.S Temeraire) and surviving the war and their brother Thomas born 1892 serving with the 2nd Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers but was killed in action 27 August 1914 and is buried at Etreux British Cemetery, Etreux, Departement de l’Aisne, Picardie, France.

| Cashman Thomas Whitegate memorial 8845, Lance Corporal, 2nd Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers. Born: 10 July 1892, Ballinrostig, Whitegate, Co. Cork. Next of kin: Mother Hannah Cashman nee Fitzgerald, Ballinrostig, Whitegate, Co. Cork. Killed in action 27 August 1914. Buried Etreux British Cemetery, Etreux, Departement de l'Aisne, Picardie, France |

William Cashman’s Naval Career

William Cashman joined the Royal Navy as a Boy Class II at Portsmouth on 1 October 1903. He gave his year of birth as 1886, for an age of 17. He did his basic training at Chatham, with a berth on the old armoured cruiser HMS Northampton and the steel corvette HMS Cleopatra. He was promoted to Boy Class I on 3 January 1904 and moved to Portsmouth later that month. When he signed on as an Ordinary Seaman to serve 12 he was 5ft 8 3/4ins tall, with dark brown hair, brown eyes and a ruddy complexion His first sea-going service was 1904-07 on the armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope (which in November 1914 was lost with all hands at the Battle of Coronel). He was promoted to Able Seaman in August 1905. He served in 1908 on the admiralty yacht HMS Enchantress, then for 12 years on the battleship HMS Swiftsure in the Mediterranean. After a six month spell at Portsmouth gunnery school he re-joined Enchantress for another year. He then spent three years and started his Great War service on the armoured cruiser HMS Minotaur on the China station. He joined HMS Hampshire after she had joined the Grand Fleet in home waters, and was promoted to Leading Seaman in July 1915. After Hampshire William returned to Portsmouth gunnery school. He signed on for another 12 years in September 1917, when his height was 5ft 10ins. He was promoted to Petty Officer on 1 November 1917 and to Acting Gunner on 6 February 1918. William continued his service with the Royal Navy until September 1919.

The following is Williams interview in 1932 to the Cork Examiner now the Irish Examiner,

A GREAT. WAR DISASTER. How H.M.S. Hampshire Was Sunk. LAST OF KITCHENER, Co. Cork Survivor Tells Graphic Story Mr. Wm. Cashman, retired warrant officer Royal Navy, now residing at Scartleigh Lower, Ballinacurra, Co. Cork, one of the few survivors of the ill-fated H.M.S. Hampshire, which sank with Lord Kitchener on board on the night of the 6th June, 1916, writes as follows:- Now, here is my account of the disaster on the memorable 5th of June, 1916, which was very stormy and cold, the bite of winter was in the air, although early summer. I was serving on board the Hampshire at the time, and in the after-noon of this date Lord Kitchener and his staff come on board our ship, we being detailed for a special mission which was to take Lord Kitchener to an unknown destination. I, personally, saw Lord Kitchener and his staff come on board, as I was on duty in connection with the gunnery department on the upper deck at that particular tine, It was blowing a gale at the time, the wind being north north-east, the wind shifting later to north-west and increasing in violence. We left harbour about 5 p.m., accompanied by two destroyers as escort, by the principal channel, Hona Sound, then steering west-wards through the Pentland Firth. We then took a northerly course to clear the Orkney's, About 7 pm, the destroyers had to abandon us as they were unable to keep pace with us when we encountered the full force of the gale off Rora Head in Hoy. They went back to harbour and we continued on our own. It was blowing a hurricane at the time and formidable seas were running, all hatches were battened and showered down on our ship, only one boing opened for admittance to and from the upper deck. The huge seas were washing over the cruiser, but there was not the slightest danger of ſoundering as she was a very good sea-boat and thoroughly seaworthy. Lord Kitchener was not on the upper deck at the time, as it was not either safe or comfortable. However, everything was in order, and the routine pipe, "Stand by hammocks," went at 8.50 p.m. THE EXPLOSION The great majority of the crew were standing by hammocks between decks when a most violent explosion occurred in the foremost part of the ship adjacent to the magazine and foremost boiler room. Numbers of the crew were badly mutilated who were close to the scene of the explosion, one poor fellow being minus every particle of flesh practically. All lights were extinguished, as the force of the explosion dismantled all electrical machinery and communications, plunging the ship into total darkness between decks, as all ports and deadlights were closed and screwed down, and hatches. Try and imagine the plight of those hundreds of men between decks and the ship settling to a most dangerous angle at the time, and only one ladder available to reach the upper deck. Lord Kitchener was at the time in his apartments, in the after part of the ship between decks, and he would have to come some distance to reach the ladder to get to the upper deck. I was between decks also, and got blown against the steel stanchion with the force of the explosion. I tried to get to Lord Kitchener's quarters but was unsuccessful, owing to the darkness and obstacles which were in my path. I gave orders then: “Make way for Lord Kitchener," but as he did not come there was only one more plan left for me to fulfil, if possible. I got up the ladder with great difficulty, as it was narrow for such a large number of men to try and get to the upper deck. On reaching the upper deck I tried to clear away the hatches, but without success, on account of the huge seas washing over the ship. I beheld a ghastly sight on this deck, dead and dying floating about and no chance of giving them relief. ON A RAFT Finally, I got trashed off the fast sinking ship, overboard and on to a raft. The ship carried three of those rafts, and those were the means of saving the twelve survivors. There were about 50 supported by my raft, and we witnessed the last scenes of the tragedy. The doomed ship sank by the bow and stood perpendicular, then took a mighty plunge and sunk beneath the waves, taking Lord Kitchener with her. My voyage on the raft threatened to be short, as the mighty whirlpool made by the sinking ship nearly carried the raft, with its complement of shipwrecked mariners, with her. This, however, was not to be, as the rafts finally drifted apart (three in number). We drifted far out to sea, as we had do means of propelling our little crafts towards the shore, our small oars, Indian canoe type, being swept away from us by the mountainous seas. Just imagine our thoughts at that moment, of loved ones at home, who many were never to meet again. Many died from cold and exposure, only four of us on my raft surviving, the clements. I attribute my life to coolness and a strong heart, and never getting excited when in a tight corner, and grasping the situation at the moment and making the best of a bad matter. There was no protection whatever from exposure and cold; we only had a network to stand on, which was attached to an oval-shaped tube which comprised the raft. I was about twelve hours on this raft, and finally we were driven towards the Orkneys. At almost any part of those huge cliffs it would be a very difficult job for a fatigued sailor to scramble up for safety. TWELVE SURVIVORS Out of the whole ships company (nearly eight hundred), there were only twelve survivors whose vitality and endurance resisted the night of the elements. We had very little reserve strength left from the buffeting of the wind and waves on that night of intense cold. When my raft reached shore the other three survivors got out rather easily as they were out in the front of the raft I was in the centre and packed round with dead comrades, and I found great difficulty in getting clear of those. The raft was on its way out to sea again when a huge sea washed me off on to the shore, so you see I was washed into the raft from the ship and I was washed out of the raft to the shore. I climbed the huge cliff then and gave the alarm, and my comrades were brought to safety by the islanders. Lyness Naval Cemetery, in the Island of Hoy, marks the last resting place of the men who succumbed to their terrible ordeal and were washed ashore. This is a brief story of the Hampshire disaster and the loss of Lord Kitchener. (Signed) William Cashman, Warrant Officer, Royal Navy (retired). Scartleigh Lower. Ballinacurra, Co. Cork. 6 April, 1932 Irish Examiner Friday 8 April 1932 |

TWELVE SURVIVORS OF THE HAMPSHIRE Washed Ashore on a Raft The Admiralty announces with regard to the loss of H.M.S. Hampshire that a further report has been received from the Commander in-Chief of the Grand Fleet that one warrant officer and eleven men have survived, being washed ashore on a raft. Their names are as follow:- Bennet, William, Warrant Mechanician. A Kirkwall telegram says the search for the survivors of the Hampshire is being continued. The survivors were found late on Tuesday night. The various reports regarding the disaster to the Hampshire which have reached Aberdeen show that Lord Kitchener arrived at a Northern destination on Monday night, and subsequently left on board the Hampshire. The vessel was lost in deep water between Marwich Head and Brough of Binsay. A telegram received in Aberdeen last night from Kirkwall stated that there were twelve survivors. Reports current are to the effect that several men who reached the shore subsequently died from exposure. The vessel sank two miles from land. A terrific gale was raging, and one boat was swamped and all aboard drowned. All bodies recovered are being removed to Stromness. Northern Whig 9 June 1916. |

Eleven of the twelve survivors of the sinking. Back row, left to right: Wilfred Wesson, Walter 'Lofty' Farnden, Alfred Read, Fred Sims (bandaged), Jack Bowman, William Phillips. Front row, left to right: Horace Buerdsell, Charles Rogerson, Dick Simpson,Samuel Sweeney, William Cashman.

“The people of the farmhouse were very kind and decent to us and attended our many wants and requirements immediately. The other two rafts of the ship came ashore some miles distant along the Orkney Coast. There were eight survivors on those two rafts and four on mine, making a total of twelve. I was the only Irish survivor, the remainder being from England, Scotland and Wales. Before retiring at night, for a long time after the disaster, I lived on the frontiers of fear, for I knew that during my few winks of sleep, I would endure again the horrors of that disaster in the form of a nightmare. Such is the story of the "Hampshire", the most terrible experience of my life.” William Cashman(Down Paths of Gold) |

On the 20 September 1921 William Cashman married my cousin Helena Cosgrove in Saleen Co. Cork. Helena’s brother, Maurice Cosgrove (M. 12378, Blacksmiths Mate H.M.S. ‘Defence’) was killed in the Battle of Jutland. William Cashman passed away 27 October 1963 and is buried in the grounds of, Church Of The Most Holy Rosary, Midleton.

CASHMAN (Saleen) On October 27, 1963 at the Bon Secours Home, Cork. William Cashman, Goleen, late W.O.R.N., Deeply regretted by his sorrowing wife and family. R.I.P. Remains will be removed on this (Monday) evening at 5.30 o'clock to Church of the Most Holy Rosary, Midleton. Requiem mass on tomorrow (Tuesday) at 11 o’clock. Funeral arrangements later. Irish Examiner 28 October 1963 |

Wilfred Wesson, with pipe, and William Cashman, another survivor. From The Great War, "I Was There".