Second Samoan Civil War And the Death of Edmund Halloran, Born Whitegate Co. Cork.

Here, then, is a singular state of affairs: all the money, luxury, and business of the kingdom centred in one place; that place excepted from the native government and administered by whites for whites; and the whites themselves holding it not in common but in hostile camps, so that it lies between them like a bone between two dogs, each growling, each clutching his own end.?

Robert Louis Stevenson

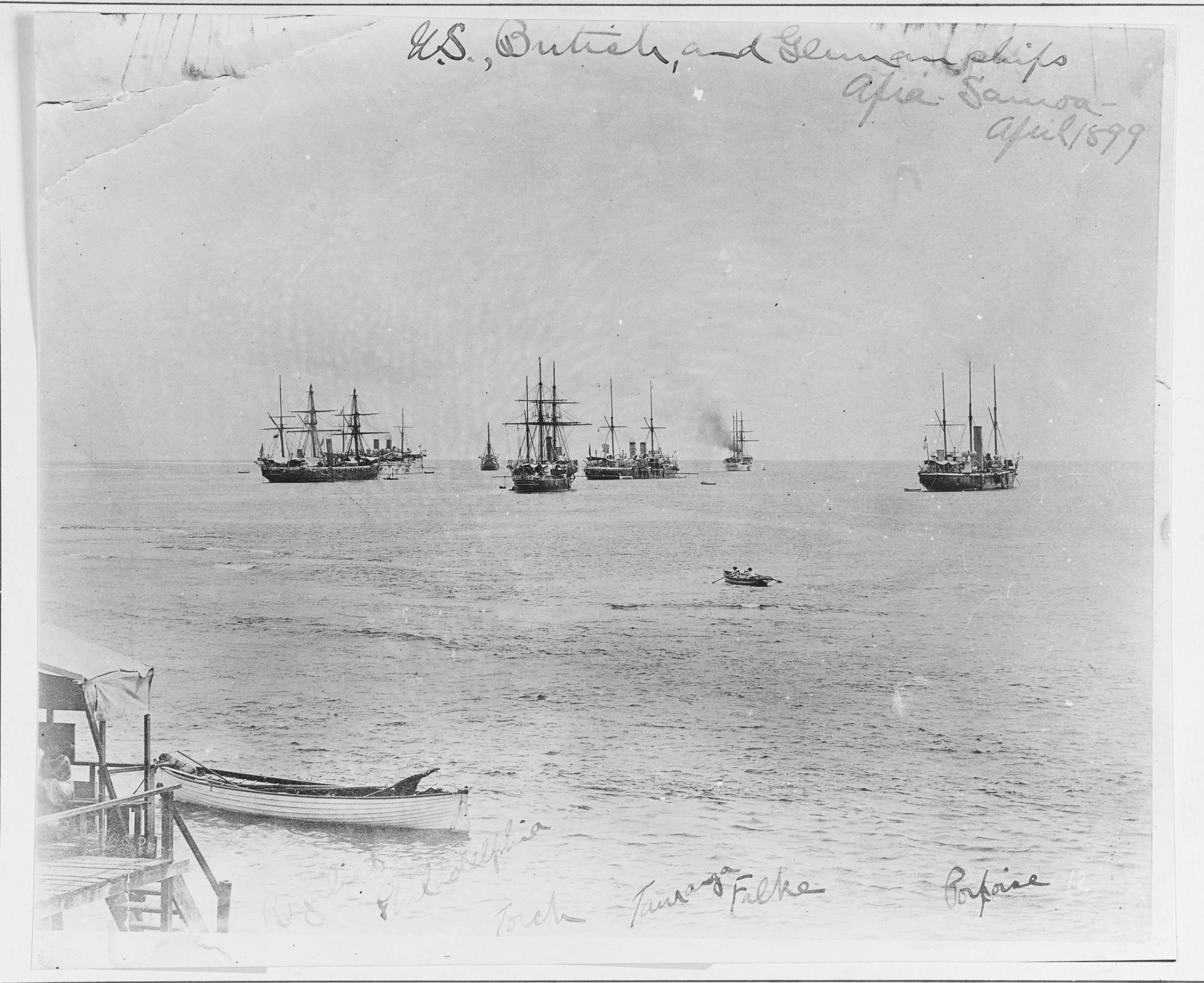

Image:H.M.S. Royalist; USS Philadelphia (C-4); H.M.S. Torch; H.M.S. Tauranga; German cruiser Falke; and H.M.S. Porpoise, at Apia, Samoa, April 1899.

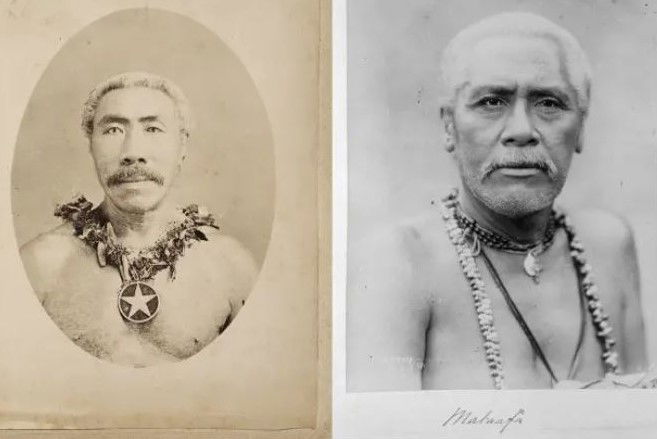

Tradition in Samoa dictated that leadership of the islands was to be invested in a hereditary chief, but in the 1880s these claims to power were anything but certain. Robert Louis Stevenson, who lived in Samoa during this period of turmoil, commented that Europeans familiar with a history of kings and queens tend to leap to the conclusion that the office of high chief is absolute. In fact the office in Samoa was elective and held in many ways on condition of the holder's behaviour and attendance to his many obligations. This confusion was to have ongoing ramifications in the late nineteenth century as European powers asserted their claims to land and political power across the three major islands of Samoa. In 1881, Laupepa was anointed king on the basis of his holding of three of the five names (Malietoa, Natoaitele, and Tamasoalii) which covered the principality of Samoa. However the other two chiefs who had claims to these highly significant titles, Tamasese who held the name Tuiaana and Mata'afa who held Tuiatua, were not completely satisfied with the arrangement. In an effort to maintain the peace each was given the role of 'vice-king' to be held for two year periods.

L-R: Tamasese Titimaea ca 1890s (PA1-q-610-38-3) and Mata'afa Iosefa ca1890 (PA1-o-546-15).

This situation provided the seeds of discord amongst the Samoans, but a greater threat to the peace of the island was the German, British and American settlers pursuing their commercial interests (particularly the German interests of the firm of Deutsche Handels und Plantagen Gesellschaft fur Sud-See Inseln zu Hamburg (DH&PG - German Trade and Plantation Society of the South Sea Islands) alongside these traditional relationships. The centre of all this activity was on the island of Upolu at the port of Apia where Samoans, Germans, Americans and Englishmen all resided. Perhaps the best description of the state of these interests is to be found at the beginning of Stevenson's book, A Footnote to History,

European intrigue exacerbated existing tensions which erupted in 1885 and led to civil war amongst the Samoans and fighting between the Germans on one side and the Americans and the British on the other. The German Counsel Dr. Stuebel entered into an agreement with Malietoa and then advocated the deposing of the existing Samoan government. However Malietoa and Tamasese secretly approached the English offering them the islands as a Protectorate. When the Germans found out they sought to replace Malietoa and, overlooking the obvious choice of Mata'afa, selected Malietoa's accomplice Tamasese as their man.

European intrigue exacerbated existing tensions which erupted in 1885 and led to civil war amongst the Samoans and fighting between the Germans on one side and the Americans and the British on the other. The German Counsel Dr. Stuebel entered into an agreement with Malietoa and then advocated the deposing of the existing Samoan government. However Malietoa and Tamasese secretly approached the English offering them the islands as a Protectorate. When the Germans found out they sought to replace Malietoa and, overlooking the obvious choice of Mata'afa, selected Malietoa's accomplice Tamasese as their man.

In September 1888 a large group of Samoans revolted against Tamasese and the German Government. By December 1888 skirmishes were erupting across the islands and tensions between the European warships in Apia harbour were at their height. On the 21 December the German ship SMS Olga shelled and burned the village of Vailele. By March 1889 the harbour was crowded with three American ships in Apia bay, the Nipsic, the Vandalia and the Trenton; three German ships, SMS Adler, SMS Eber and SMS Olga; and one British, HMS Calliope. In addition there were six merchant ships, ranging from twenty five to five hundred tons, and a number of small craft which further encumbered the anchorage. On 15 March a hurricane struck and the SMS Eber went down on the reef with nearly 80 drowned. The USS Nipsce was beached on the sand escaping with a few lives lost, SMS Adler was lifted onto the reef which broke her back and twenty lives were lost, USS Vandalia also went down in the storm after colliding with the SMS Olga losing 43 lives, while USS Trenton only lost one life.

The Germans in the wake of this disaster agreed again to talks with the British and the Americans. This allowed tensions to quieten down and a treaty document was signed in which Malietoa was recognised as king by the European forces. However this was against the wishes of many Samoans who saw another chief, Mata'afa, as the real hero of the conflict. The agreement also established an accord for the tripartite supervision of the islands, but unfortunately for all involved, it appears to have been constructed in haste and the resulting document led to squabbles and by 1892 the island still lacked any form of peace, order and effective administration.

Tamasese had died in 1891 and in 1893 another civil war broke out between Mata'afa and Malietoa, the upshot of which was the capture and deportation of Mata'afa. In 1894 fresh conflict broke out between Tamasese's son and Malietoa which was put down by German forces.But in August 1898 Samoa's King Malietoa Laupepa died and his long-time rival Mata'afa returned from exile supported by the German forces. This act was strongly opposed by the British and Americans who backed Laupepa's son, Tanu, and in January 1899 a war, similar to the one ten years previously, erupted in Apia. In an astounding turn of events the American heavy cruiser U.S.S. Philadelphia shelled Apia on 14 March almost ten years to the day of the anniversary of the hurricane which ended the first conflict.

Siege of Apia and the Death of Edmund Halloran

On March 15, Rear Admiral Kautz sent the Mataafa another message, this time he demanded that the Mataafans leave the outskirts of the town. This message was ignored and instead Mata'afa Iosefo increased the numbers of his men around Apia and attacked. The British and American commanders estimated that a total of over 4,000 rebel warriors armed with 2,500 rifles opposed them. Over the course of the siege there were approximately 260 British and American servicemen involved, fighting with approximately 2,000 friendly Samoan warriors. Apia referred to the main settlement which was surrounded by several nearby villages. The Americans held the Tivoli Hotel in Apia, which was used as their command post, sentries were also placed at the consulates which were fairly isolated according to reports and mostly surrounded by dense jungle. At twelve thirty am, the Mataafans rushed the British and American consulates guarded by sailors and marines under Lieutenant Guy Reginald Archer Gaunt of HMS Porpoise and Captain M. Perkins of the United States Marines. Though the British and Americans held their fire, the Samoans retreated after realizing that Apia's garrison was on high alert and prepared for battle.

This photograph is of people in the street outside the Tivoli Hotel in Apia which Mata'afa's supporters attacked in March 1899. Object No. 85/1284-1479

Just before one pm, rebel boats were spotted off Vaiusu and were thought to be making an attack on the Samoan refugees in the village of Mulinuu. At this time, Kautz was informed of the assault on the consulates so he gave the order to open fire on the boats and on the Mataafa's front line. All three of the British and American warships began bombarding the boats and the outskirts of Apia until five pm, when HMS Porpoise was detached alone to shell the Vaiusu and Vaimoso villages. Several boats were sunk that day and hundreds of shells expended. The Mataafans decided to attack the American held hotel the following night on March 15. During this assault, the Samoan rebels advanced hastily and temporarily captured a seven pounder artillery piece before being repulsed by fire from both the garrison and the warships. During these skirmishes, five sailors were killed, Americans Private Thomas Holloway U.S.M.C and Private John Edward Mudge U.S.M.C from the U.S.S. Philadelphia, Able Seaman Andrew Henry Joseph Thornberry from Ballybricken, Co. Waterford, Ordinary Seaman Montague Rogers from Cornwall England and Ordinary Seaman Edmund Halloran from Whitegate Co. Cork from H.M.S. Royalist. The Samoan casualties were unknown. From then on until the end of the siege, the fighting took the form of sniping and skirmishing. Mataafa's army continued to occupy the outskirts of Apia and many of the surrounding villages. Thus the Allied force came to the conclusion that they had to combine their strength and attack the Mataafan's front line or wherever they were in large numbers. By engaging the rebels in a decisive action, they would be forced to abandon the siege.

On March 24, the cruiser HMS Tauranga under Captain Leslie Creery Stuart arrived at Apia, Captain Stuart then took command of British naval operations in Samoa. The final engagement occurred on March 30 when the British, American and Samoan loyalists marched south to confront Mataafa. Three miles south of Apia, the Allies under the command of Lieutenant Gault attacked and routed a large rebel force. Twenty seven Mataafans were counted dead with a loss of three more Britons, one American sailor and one Samoan warrior, and several others were wounded. After this, the rebels retreated to their main stronghold of Vailele, southeast of Apia. During the siege the German consulate was hit by shell fire and later its occupants protested the American and British use of force in Samoa. Tanu's forces were significantly outnumbered by Mata'afa's on the island of Upolu, putting the former in a precarious position. In response, British and American ships intervened by gathering hundreds of Tanu's supporters from the neighbouring Samoan islands of Savai'i and Tutuila. These reinforcements were transported to Apia, where they were armed, trained, and prepared for battle. The situation had reached a critical point as the conflict, part of the Second Samoan Civil War, was escalating.

On March 30, 1899, a combined British and American force, commanded by Commander Frederick Charles Doveton Sturdee, advanced along the coast of Upolu. Sturdee’s force included approximately 100 Samoan fighters under the command of Lieutenant Gaunt. Their objective was to push back Mata'afa's forces and re-establish control in the region. The allies moved from Apia toward Vailele, a plantation that had been a key battleground during the First Samoan Civil War in December 1888. As they advanced, they encountered small groups of Mata'afa's men, who were quickly driven back along the coastline. The allied forces, determined to break Mata'afa's resistance, skirmished with his men along the way, and in the process, they destroyed two villages believed to be loyal to Mata'afa. These villages were suspected of providing support to Mata'afa's forces, and their destruction was intended to cut off any further assistance. By April 1, 1899, the British, American, and Samoan allies shifted their focus inland. They turned away from the coast, entering the dense jungle that surrounded Vailele, where they intended to launch a direct assault on the plantation, a stronghold of Mata'afa’s forces.

During this time, the British warship HMS Royalist provided crucial naval support. It shelled two Samoan outposts situated along the coast, both of which had served as warning stations, alerting Mata'afa's forces of potential attacks from the sea. The bombardment from Royalist was meant to neutralize these outposts and limit Mata'afa's ability to respond effectively to allied movements. However, as the allies ventured further inland into the thick tropical jungle, they moved beyond the range of naval gunfire, leaving them vulnerable to attack. As the allied column advanced deeper into the jungle, nearly 800 of Mata'afa's warriors launched a surprise attack. The assault targeted the rear-guard and left flank of the column, catching the allied forces off guard. In response, the British and American troops quickly established skirmish lines and returned fire. They also deployed a Colt-Browning M1895 machine gun to suppress the Samoan attack. However, the situation rapidly deteriorated when many of the Samoan levies, who had been fighting alongside the British and Americans, began to desert, leaving their allies in a perilous situation. Amid the chaos of battle, Mata'afa's warriors managed to shoot and kill Lieutenant Angel Hope Freeman of H.M.S. Tauranga. With Freeman down, command of the allied forces fell to Lieutenant Phillip Lansdale of U.S.S. Philadelphia. The fighting grew increasingly desperate, with Samoan snipers hidden in the dense jungle foliage inflicting heavy casualties on the allied forces. Some of Mata'afa's men also closed in on the allied troops, engaging in brutal hand-to-hand combat.

At a critical moment in the battle, the Colt machine gun jammed, leaving the allies without one of their key weapons. Lieutenant Lansdale attempted to clear the jam, but he was struck by a bullet in the thigh and fell to the ground, severely wounded. Recognizing the dire situation, Lansdale ordered his men to retreat. Despite his injuries, he urged them to leave him behind and save themselves. However, Ensign John R. Monaghan, displaying extraordinary courage, refused to abandon his commander. Monaghan grabbed a rifle from a disabled soldier and, along with Seaman Norman Eckley Edsall and two other men, attempted to carry the wounded Lansdale to safety. As they struggled to move Lansdale, the Samoan forces closed in. Edsall was shot and killed, and despite Lansdale’s repeated pleas for his men to abandon him, Monaghan continued to stand by his side. In a remarkable act of bravery, Monaghan defended Lansdale with his rifle, but he was outnumbered by Mata'afa's warriors. One survivor later recounted that Monaghan "stood steadfast by his wounded superior and friend; one rifle against many, one brave man against a score of savages." Monaghan knew his fate was sealed, but he refused to yield. He died heroically in his attempt to protect his commander.

As the situation became increasingly hopeless, the Royalist resumed its bombardment, firing into the jungle in an effort to cover the retreat of the remaining allied forces. The naval shelling provided some relief, allowing the surviving members of the column to withdraw from the battlefield. However, the toll of the battle was heavy. Four Americans were killed, and five others sustained injuries. Among the British forces, three soldiers lost their lives, and two were wounded. In contrast, the losses among the Samoan levies, who had largely deserted, were minimal. Mata'afa's forces, however, suffered significant casualties, with approximately 100 of his men killed or wounded. Despite the heavy losses and the chaotic retreat, there were acts of exceptional heroism during the battle. Three U.S. Marines, Sergeant’s Michael Joseph McNally, Bruno Albert Forsterer and Private Henry Lewis Hulbert, were awarded the Medal of Honour for their bravery and extraordinary actions during the engagement.

War Department, General Orders No. 55 (July 19, 1901)

CITATION: The President of the United States of America, in the name of Congress, takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to Sergeant’s Michael Joseph McNally, Bruno Albert Forsterer and Private Henry Lewis Hulbert United States Marine Corps, for distinguished conduct in the presence of the enemy while serving with the Marine Guard, U.S.S. Philadelphia in action at Samoa, Philippine Islands, 1 April 1899.

Among those who perished during the battle on April 1st were Lieutenant Phillip Lansdale, Ensign John R. Monaghan, Coxswain James Butler from Kereen (Aglish), Co. Waterford and Ordinary Seaman Norman Eckley Edsall, all of U.S.S. Philadelphia. From the British side, Leading Seamen John Long from Monkstown, Co. Dublin and Albert Meirs "Bert" Prout from Cornwall England of H.M.S. Royalist were killed, along with Lieutenant Angel Hope Freeman of H.M.S. Tauranga.

Ordinary Seaman Norman Eckley Edsall had two ships named in his honour. The first was the U.S. Torpedo Boat Destroyer No. 219, named Edsall, which was christened by his sister Bessie on July 29, 1920, at Cramp Shipbuilding Co. in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Their adoptive mother, Alwilda Edsall, and Bessie’s husband, Lewis, were also present for the ceremony. The second ship, DE-129 (Destroyer Escort), was launched on November 1, 1942, by Consolidated Steel Corp. in Orange, Texas. This vessel was also christened by Bessie, accompanied by their sister Jeannie (Brainerd) Lowe.

In the aftermath of the battle, the situation on Upolu reached a stalemate. While the British, American, and Samoan forces managed to establish control along the coast, Mata'afa's forces, supported by the Germans, remained entrenched in the island's interior. The conflict continued to drag on, with both sides suffering losses but making little progress. Though the casualties from the April 1st encounter were relatively small, with only seven dead, historian Paul Kennedy, in his work The Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations 1878–1900, noted that these losses were "remarkably light considering the circumstances." The events of the battle further complicated the already tense political situation in Samoa, as the conflict involved not only local factions but also international powers vieing for influence in the Pacific. The outcome of the Second Samoan Civil War would shape the future of the islands and the balance of power among the colonial powers in the region.

The inevitable deadlock was broken by a ceasefire announced on 25 April and in May 1899 a specially set up commission of British, American, and German representatives arrived. Soon after a treaty was agreed to by all parties. This document recognised the independence of the Samoan Government and divided European interests so that Germany received the western Samoan islands with Savaii and Upolu, the United States received the eastern islands with its capital at Pago Pago on Tutuila and Britain withdrew from the area for recognition of rights on Tonga and the Solomon Islands.

Graves of American and British soldiers killed in action during the Samoan civil war of 1888-1899. Photograph taken by Alfred John Tattersall, circa 1899.